45 Minutes Was Spent Face to Face With the Family by a Counselor Providing Genetic Counseling

Abstruse

Purpose: Patients seeking genetic testing for inherited breast cancer risk are typically educated by genetic counselors; however, the growing demand for cancer genetic testing will likely exceed the availability of counselors trained in this area. We compared the effectiveness of counseling alone versus counseling preceded by use of a computer-based decision help among women referred to genetic counseling for a family or personal history of chest cancer.

Methods: We developed and evaluated an interactive computer program that educates women nearly breast cancer, heredity, and genetic testing. Betwixt May 2000 and September 2002, women at six study sites were randomized into either: Counselor Group (n = 105), who received standard genetic counseling, or Computer Group (n = 106), who used the interactive reckoner program before counseling. Clients and counselors both evaluated the effectiveness of counseling sessions, and counselors completed additional measures for the Computer Group. Counselors besides recorded the elapsing of each session.

Results: Baseline characteristics did not differ significantly between groups. Participants and counselors both rated the counseling sessions every bit highly constructive, whether or not the sessions were preceded past computer utilise. Computer employ resulted in significantly shorter counseling sessions among women at low adventure for carrying BRCA1/2 mutations. In approximately half of the sessions preceded past clients' computer utilize, counselors indicated that clients' use of the computer programme afflicted the way they used the time, shifting the focus away from basic education toward personal take chances and decision-making.

Decision: This study shows that the interactive computer program "Chest Cancer Risk and Genetic Testing" is a valuable adjunct to genetic counseling. Its use before counseling tin shorten counseling sessions and allow counselors to focus more on the clients' individual risks and specific psychological concerns. As the need for counseling services increases, a program such as this can play a valuable role in enhancing counseling efficiency.

Main

In the past decade, at that place has been an unprecedented explosion of genetic discovery, culminating in the complete sequencing of the man genome in April 2003.1 Molecular tests now allow evaluation of a person'south genetic susceptibility to various cancers, and as more conditions are identified for which genetic testing can be performed,2–iv it is inevitable that genetic testing will be used more frequently to make predictive, diagnostic, and risk management decisions.5,half-dozen In fact, genetic tests are at present marketed directly to physicians and to the public, increasing the frequency of patients' requests for testing from their physicians.nine Even so, it is well-documented that primary intendance physicians' knowledge and comfort levels with genetic data are limited.8–10 Without acceptable agreement of the strengths and limitations of genetic testing, many patients may undergo genetic testing that is non necessary or informative and may, in fact, be ill brash.11–sixteen

Thus, there is a consensus in the genetics community that patients who are considering genetic testing for inherited cancer risk should be educated nigh risks, benefits, and alternatives before existence tested.17 This education is typically provided by genetic counselors trained in cancer genetics. Withal, with approximately 1800 board-certified genetic counselors in the Usa,18 and fewer than 400 genetic counselors who list cancer every bit their specialty,xix the growing need for cancer genetic testing volition probable exceed the availability of counselors trained in this area.xx–22 Consequently, alternative or adjunct educational resources are necessary to assistance see the educational needs of individuals who seek cancer genetic counseling and to enhance the genetic counseling process.

The need for authentic information about genetic aspects of breast cancer is specially pressing. Breast cancer is the most commonly occurring nonskin cancer amidst women, and it is estimated that 215,000 women volition develop invasive breast cancer and more 40,000 will die from information technology in 2004.23 Approximately 7% of breast cancer cases are associated with an autosomal dominant blueprint of inheritance,24 and of these, 84% are associated with mutations in the breast cancer-susceptibility genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 25 for which genetic testing is clinically available.

To address this growing demand, we developed an interactive computer-based decision assistance ("Breast Cancer Run a risk and Genetic Testing") to educate women considering genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility.26,27 The program is a multimedia, interactive conclusion aid designed to assist people make informed decisions about genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility and was adult by an interdisciplinary squad of educators, physicians, genetic counselors, and scientists. It is organized into three sections: Section 1 provides a brief overview of breast cancer, Section ii discusses chest cancer genetics, and Section 3 addresses factor testing for breast cancer. In each section, a serial of questions and answers guide the user through the content material. The general structure is for a simulated "patient" to ask a question (for example, "what is breast cancer?") and and so for an "expert" narrator to provide an respond. The questions are asked by various women of diverse backgrounds, while the answers are given by one female expert. In our early experience piloting the CD-ROM with a various group of women (unreported data), we observed that each user would navigate through the programme differently, focusing on her detail areas of interest.

In an initial clinical trial, we establish that the program was well-accepted by genetic counselors and their clients,28 and its apply increased clients' knowledge about breast cancer genetics and decreased their intention to undergo testing.29

Afterward, we revised and updated the calculator program and conducted a larger, randomized, multicenter trial among women referred for genetic counseling due to family or personal histories of breast cancer.xxx In this article, we written report findings from one attribute of that study that compared the effectiveness of counseling lone with counseling preceded by computer utilize. The study questions were every bit follows: (1) From the clients' perspective, were counseling sessions supplemented by a reckoner program more effective than standard counseling sessions? (2) From the genetic counselors' perspective, were counseling sessions supplemented past computer more effective than standard counseling sessions? (3) Compared to standard genetic counseling, was counseling supplemented by reckoner: (a) more efficient, (b) shorter in elapsing, and (c) dissimilar with regard to content? Answers to these questions are important, equally they may shed calorie-free on the potential applicability and implementation of this program in other settings and with other health care providers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Between May 2000 and September 2002, women who had been referred to a genetic advisor for evaluation of breast cancer gamble were recruited to participate in a trial to compare the effectiveness of computer-based counseling with face-to-face genetic counseling. There were six study sites in this trial (Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey PA; Lehigh Valley Hospital and Wellness Network, Allentown, PA; The University of Texas Dr. Anderson Cancer Middle, Houston, TX; Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX; University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA; and Evanston Northwestern Health Intendance, Evanston, IL.). The protocol received Institutional Review Lath (IRB) approving at each of the participating sites and was monitored past each local IRB. Women were eligible to participate in this study if they were xviii years of age or older; could read, write, and speak English; scheduled a genetic counseling engagement to evaluate personal and/or family histories of chest cancer; and were able to give informed consent. Women who previously underwent genetic counseling or testing for inherited breast cancer susceptibility were excluded.

Blueprint and procedures

This was a randomized trial comparison the effectiveness of genetic counseling alone with counseling supplemented by computer use from the perspectives of both clients and counselors. Participants (clients) were randomized into one of two groups earlier the actual date of their genetic counseling appointment: (ane) Counselor Grouping (n = 105), who received standard genetic education and risk cess by genetic counseling professionals, and (2) Computer Group (northward = 106), who used the interactive estimator program before their genetic counseling sessions. To ensure that equal numbers of loftier- and low-adventure women were included in both arms of the study, each study site maintained 2 dissever randomization lists: ane for women at high risk of carrying a BRCA1/ii mutation (≥x%) and one for women at low adventure (<10%) as calculated using the BRCAPRO model.31–34

Before their counseling appointments, participants provided written informed consent and completed baseline questionnaires. Participants who were assigned to the Advisor Group proceeded directly from baseline information collection to their genetic counseling appointments. Participants assigned to the Reckoner Grouping were directed by project staff to an area where they could utilize the computer program. Afterward completing the program and some questions, these participants proceeded to their genetic counseling sessions. Immediately afterwards counseling, participants in both groups completed identical postintervention questionnaires. Counselors besides completed postsession questionnaires at that time, including items virtually the impact of computer use on the counseling sessions. For this reason, the counselors were not blinded equally to clients' report group assignments.

Interventions

Reckoner-based educational intervention

The computer program ("Breast Cancer Risk and Genetic Testing") is an interactive, multimedia, CD-ROM decision aid designed to brainwash women about breast cancer, heredity, and positive and negative aspects of genetic testing. It has been described in detail elsewhere27 and has received positive reviews in the medical literature.35–39 The program'southward main purpose is to assist women make informed decisions nigh BRCA1/2 genetic testing and includes information about chest cancer run a risk, the part of heredity in the development of breast and ovarian cancers, and the benefits and limitations of genetic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. It is easy to use, requires no prior experience with computers, and was designed for women of unlike ages and educational levels. Considering it is self-paced and user-driven, each user determines the sequence of accessing various sections, as well every bit the corporeality of time spent on each section. In this study, participants spent on boilerplate 45 to 60 minutes using the programme.

Genetic counseling

Genetic counseling was provided by 12 certified genetic counselors and one advanced practice nurse with specialty training in cancer genetics, collectively referred to as "counselors." Investigators and counselors agreed upon a ready of topics to be discussed during the counseling sessions based on accepted guidelines,40 and these topics corresponded to the estimator plan's content. Unlike the computer plan, genetic counseling sessions also included individualized risk estimates of the likelihood of conveying a gene mutation, and psychosocial support to address emotional concerns related to breast cancer risk and genetic testing.

Measures

At baseline, participants were asked about demographic characteristics and experience with computers. Medical literacy was assessed using the Rapid Gauge of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM), a reliable and valid measure to provide an estimate of a person's reading ability with regard to medical terminology.41 Personal and family cancer history information was collected before the counseling appointment, and counselors used the BRCAPRO model31–34 to summate each participant'due south estimated risk of carrying a BRCA1 or BRCA2 germ-line mutation. After the counseling sessions, the following outcome measures were administered to both groups.

Effectiveness of session

The perceived overall effectiveness of the counseling sessions was assessed with a single question completed by both research participants and counselors: "Overall, how effective was this session with the (genetic counselor/client)?" Response options ranged from i (Not at all effective) to 7 (Extremely constructive). Additionally, participants and counselors were asked to rate 12 attributes of the counseling session, including the following: clients' willingness to share worries and fears; their understanding of breast cancer, heredity and genetic testing; their preparedness for making a determination about testing; the quality of questions asked; the level of rapport with the counselor; and the extent to which emotional and informational needs were met. Response options ranged from ane (Poor) to 4 (Excellent).

Elapsing of counseling sessions

The amount of time each participant spent in the counseling session was recorded by the genetic counselor.

Impact of calculator apply on the counseling session

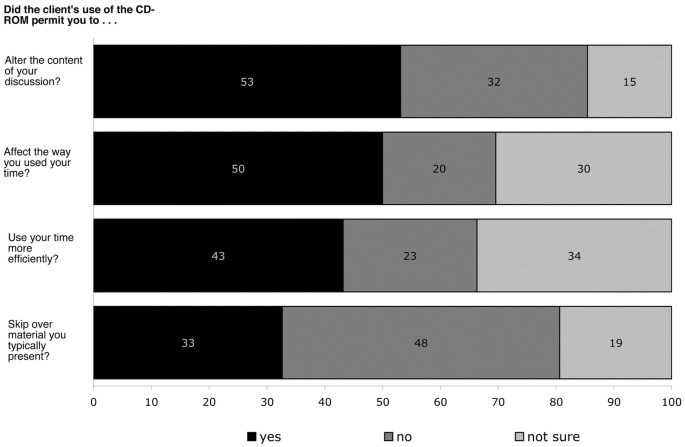

Counselors were asked to assess the impact of the computer program on the genetic counseling sessions by answering iv questions: (1) Did the client'south use of the CD-ROM allow you to skip over material you typically present? (ii) Did it help you to use your time more efficiently? (iii) Did information technology change the content of your word? (four) Did information technology impact the way you used your time? Response options were "Yes," "No," and "Not sure," followed by space for explanatory comments.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables. Group differences in continuous outcomes such as age, REALM score, and length and quantitative effectiveness of counseling sessions were assessed by t tests. Grouping differences in categorical and ordinal outcomes such every bit race, estimated risk of mutation, and Likert scale responses were assessed by Chi-square test. 4- and five-point Likert scale responses were analyzed every bit ordinal outcomes. These responses were collapsed into a smaller number of categories when one or more than levels had fewer than 5 responses. All analyses were performed using the SAS statistical software system version 8.1 (SAS Constitute, Cary, NC).

The open-ended responses were analyzed using qualitative methods to identify emergent themes related to the enquiry questions.42 The investigators created a coding scheme by reviewing responses and identifying common themes. Using an iterative process, two investigators sorted responses into categories, reducing the categories to a manageable number. Characteristic responses were identified and quotations were included verbatim, excluding names to protect confidentiality. Themes and findings from the analysis also underwent contained review by other study investigators.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

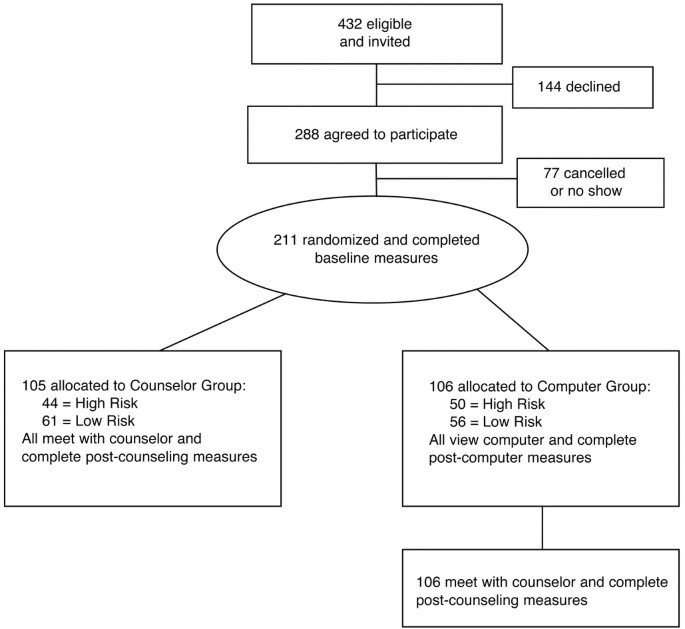

Of 432 eligible women who were invited to participate in this written report, 288 agreed, 77 did not go along appointments, and 211 were randomly assigned to either the Computer Group or the Counselor Group (Fig. ane). Baseline characteristics did non differ significantly between the Figurer and Counselor Groups (Table one). Participants' mean age was 44 years, 74% were < 50 years sometime, 56% had completed college or across, and 93% were white. Thirty-nine pct reported existence "very confident" with their calculator skills, 64% reported using a computer "often" at home or at piece of work, and 42% reported having heard or read "a fair corporeality" or "a lot" near genetic testing. Mean REALM scores indicated a loftier level of familiarity with medical terms (65 on a scale from 1 to 66). Based on BRCAPRO estimates, 55% of participants had less than a 10% take chances of conveying a mutation (depression take chances) and 45% of participants had a 10% or greater chance (high take a chance). Low and high risk individuals were similar with respect to most baseline characteristics, only high-hazard individuals were younger (42 vs. 47 years; P < 0.003) and more familiar with genetic testing (50% vs. 36% reported having read or heard "a fair amount or a lot" about genetic testing; P = 0.04).

Pattern of the report and subject participation.

Effectiveness of the counseling session

Participants and counselors both rated the counseling sessions as highly effective overall, whether or not the sessions were preceded by computer use (Table 2). The hateful effectiveness rating by participants (on a scale of ane–7) was 6.6 in both the Counselor and Computer Groups. Counselors also rated the sessions as highly effective, although less so than the participants (P < 0.001). Participants' ratings of the effectiveness of the session did not differ based on risk condition.

In addition to an overall effectiveness rating, participants and counselors also rated 12 specific attributes of the counseling sessions. On 11 of 12 items, participants one time again rated the effectiveness of the sessions significantly college (P < 0.0001) compared with the counselors (Table iii). Participants' responses did non differ by grouping status or by run a risk status. Likewise, counselors' responses for 11 of 12 items did non differ by participants' grouping status; nonetheless, they indicated that clients in the Reckoner Group had a better understanding of heredity than those in the Counselor Group (P = 0.03).

Duration of counseling sessions

Overall, estimator plan employ resulted in shorter face up-to-confront counseling sessions (90 minutes in the Counseling Group vs. 82 minutes in the Computer Group; P = 0.03). When analyzed past risk status, this reduction in the elapsing of counseling sessions was meaning among women at low risk for carrying BRCA1/two mutations (89 minutes in Counselor Group and 77 minutes in the Computer Group; P = 0.027), but not among those at loftier hazard (91 vs. 86 minutes; P = 0.39).

Bear upon of the estimator program on provision of counseling

In approximately half of the counseling sessions involving the Computer Grouping, counselors reported that clients' computer utilise permitted them to alter some attribute of their typical counseling practices. Specifically, it permitted counselors to do the following: modify the content of discussions in 53% of sessions; change the way they used their time in 50% of sessions; utilise their fourth dimension more efficiently in 44% of sessions; and skip material they typically nowadays in 33% of sessions (Fig. ii). These findings were like for high- and low-risk women. Counselors' comments (see post-obit sections) explained how the computer programme afflicted the counseling sessions.

Touch of reckoner use on the counseling session. Pct of counselors indicating "aye," "no," and "not sure."

Impact of the computer program on content of word during counseling session

30 2 percentage of the counselors indicated that they did non change the content of their counseling discussions with Calculator Group participants. However, most counselors (53%) reported that they did modify the content of these discussions, and described two master ways in which they did and so. First, participants' use of the computer earlier the session immune counselors to shift the focus of discussions away from explanations of basic genetic concepts, and toward the specific concerns of individual clients. For example: "spent more time focusing on (the) programme, not on educational activity"";(spent) less fourth dimension talking nigh chromosomes, genes, cancer risks, BRCA1/ii"; and "allowed more time to address her specific health concerns." Second, counselors commented that the figurer plan raised clients' sensation of certain problems, prompting counselors to address questions stimulated past the program: "patient asked questions about insurance discrimination based on what she saw in computer plan"; and "patient formulated questions based on information in CD-ROM."

Impact of the figurer plan on utilise of time during counseling session

Counselors indicated that they altered the way they used their time in 50% of the sessions preceded by computer utilise. In particular, counselors indicated that apply of the programme by these clients immune them to redirect the emphasis of the sessions to specific bug identified by clients. For example: "more time… spent discussing ambivalence with regard to pursuing genetic testing"; "more time on clinical issues and medical surveillance..."; "more time spent on discussion of state and federal laws"; "moved into psychological issues more speedily than usual"; and "more fourth dimension was spent on the implications of genetic testing for her and for her family." For nearly fourscore% of the clients in the Calculator Group, employ of the computer program besides shortened the amount of time needed for contiguous counseling.

Counselors indicated that they did not change the style they used their time in about 20% of Computer Group sessions. A common explanation was that counselors felt an obligation to review all topics they typically reviewed, regardless of the clients' baseline knowledge.

Touch on of the computer program on efficiency of the counseling session

Counselors reported that the reckoner program helped them utilise their time more efficiently in 43% of sessions and characterized this efficiency in 3 ways: (1) shifted the focus of discussions to the participants' specific concerns, (two) reinforced concepts that were already presented past the computer, and (3) spent less time providing basic information near genetics.

For example, a shift in focus to clients' specific concerns was illustrated by comments such equally the following: "more focused give-and-take on customer's family history and more cursory explanation of genetics"; "more time to address client's concerns for ovarian cancer risks"; and "able to accost the psychosocial concerns since she had a skillful agreement of the factual info."

Counselors as well reported that sessions were more efficient considering many concepts already had been introduced by the figurer program: "I believe we went through the information more than efficiently because patient had seen the CD"; "it helped that the patient was already introduced to some basic concepts"; and "I remember it helps that the patient had already heard the information once."

Finally, counselors reported that sessions were more efficient because they did not demand to spend every bit much time providing basic information: "spent less fourth dimension on the groundwork data"; "minimized the need for lengthy word near genetics"; "some things could exist skipped"; and "was able to go through teaching more quickly."

Counselors indicated that the figurer programme did not help them use their time more efficiently in 23% of sessions, and they were not sure whether the programme impacted efficiency in 34% of sessions. One theme that emerged in regard to this response was that involvement in this research study sometimes increased the overall amount of fourth dimension that counselors needed to be available to clients compared to their standard sessions, due to the added steps and responsibilities required by the study protocol. For example: "It shortened the face-to-face fourth dimension, but lengthened the amount of time I needed to exist available to the patient"; [efficiency was not improved] "considering of the waiting between scheduled time and bodily face time."

Impact of the reckoner plan on the blazon of information presented during the session

Counselors reported that they skipped information that they typically presented in 33% of sessions preceded past computer employ. The computer program seemed to influence the amount of information that counselors presented almost genetics and heredity, every bit illustrated by the following comments: "allowed me to use less detail in my descriptions"; "allowed me to spend less time explaining BRCA1/2"; "allowed me to bypass in-depth give-and-take of modes of inheritance"; "abbreviated give-and-take of genes, heredity, AD inheritance"; and "I was able to skip over a lot of the information on basic genetics."

DISCUSSION

Genetic counseling for cancer predisposition is a circuitous and labor-intensive endeavor, involving provision of data, evaluation and discussion of individual adventure factors, and counseling about psychosocial concerns.5,43,44 Every bit the demand for cancer genetic counseling increases in response to the rising availability of genetic testing, it will become more important to provide education and counseling in an efficient and constructive manner.

The present study demonstrates that an interactive computer program can ameliorate counseling efficiency by shortening the duration of sessions while enabling the counselors to focus on the clients' individual concerns. Because the computer program is effective at providing basic data, it enables counselors to spend their time addressing other important aspects of the counseling process,44 such every bit assessing individual risk, providing psychosocial support, and aiding decision-making.

It is encouraging to note that from the clients' point of view, the genetic counselors in this study did their task exceedingly well, and this perception was consistent across intervention groups. Participants rated the counseling sessions very highly overall, as well as on specific attributes such every bit the following: willingness to share worries and fears; understanding of cancer, heredity, and the pros/cons of genetic testing; preparedness for making a decision; the extent to which emotional and factual concerns were addressed; and rapport and satisfaction with the counselors and the counseling.

Although counselors likewise regarded the counseling sessions as largely effective, it is interesting to note that the participants consistently rated the sessions higher than did the counselors. 1 possible explanation for this finding is that clients inflated their ratings of the counselors by providing socially desirable responses rather than expressing their true feelings.45 Another possible caption is that the responses may reverberate a difference in expectations. That is, participants may have been pleasantly surprised past how much they had learned, but counselors may accept wished they had achieved more during the session and thus were comparatively less satisfied.

We had hypothesized that, compared with standard counseling, the use of our computer program before counseling would issue in significantly higher effectiveness ratings from the perspectives of both clients and counselors. However, because the effectiveness ratings of counseling sessions were uniformly loftier without computer apply, the improver of the programme did not significantly raise scores. Nevertheless, the computer programme was effective in several specific ways. According to the counselors, clients' utilise of the reckoner permitted tailoring of the content of many discussions and thereby increased counseling efficiency in the majority of sessions. Counselors specially noted that clients' figurer use resulted in shorter counseling sessions, more than focused education, and the opportunity to better address the participants' individual concerns.

Although use of the computer program shortened face-to-face fourth dimension with the counselors amidst low-risk women, it is important to notation that its use increased the overall time of report visits. This is not surprising, because using the computer program as part of a study protocol required an additional hour of educational activities. Whether more time would be necessary outside a study is not known. Even so, if counselors are to increase their capacity in the clinic, information technology will be necessary for them to exist able to predict in advance which clients would require less time. Future research can accost whether using the program at abode in advance of the counseling visits would be beneficial to clients and would result in shorter counseling sessions.

A couple findings warrant further comment. Counselors indicated that the computer plan did not lead to more efficient use of their fourth dimension in 23% of sessions, and were not sure of its bear upon on efficiency in 34% of sessions. Because participation in a research trial involves extra time for scheduling and information collection, it is possible that these responses reflected the burden imposed by research-related tasks. This is an important methodological issue to address when designing futurity genetic counseling intervention studies.

Similarly, in 48% of the sessions, counselors said the computer plan did not let them to skip over textile they typically present. These results are largely explained by the responses of a single genetic counselor, who indicated 29 times that although the CD-ROM was useful, (s)he did not feel comfortable altering his/her normal design of interaction with clients merely because they were enrolled in a research study. It would therefore be interesting to know whether the calculator program would have a different impact outside the research setting.

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. The overall effectiveness of the counseling session was assessed with a single question answered past both participants and counselors. Such a global effectiveness score may lack sensitivity to detect subtle differences in counseling effectiveness. Consequently, the results may reflect a limitation of the tool rather than the computer program. Second, because this was non a blinded study, counselors knew which participants had and had not used the computer program. As such, counselors' responses may have been biased.

Third, our results may not be applicable to other populations. Of 432 eligible women, almost half participated in the study, and we accept no information about those who declined. The women who enrolled in the written report were predominantly white, relatively immature (mean historic period 44 years), well educated, and comfortable with using computers. Whether these were "typical" clients seeking genetic counseling for breast cancer susceptibility is not known, and the utility of the reckoner program for a more than diverse population remains to be shown.

Despite these limitations, this written report shows that our interactive computer program "Breast Cancer Risk and Genetic Testing" is a valuable adjunct to genetic counseling. Its use before counseling non merely shortens some counseling sessions, simply more chiefly, frees counselors to spend their time discussing the clients' individual risks and specific psychological concerns. As the demand for counseling services increases, a program such every bit this can play a valuable function in enhancing counseling efficiency, peculiarly with those at low risk for carrying a gene mutation. Ultimately, the program may have its greatest impact equally an educational resource for primary care providers, who are situated to decide which of their patients can benefit well-nigh from the services of a genetic counselor, and which may be adequately served through alternative educational measures. As a grouping currently unprepared to meet the needs of patients seeking information nearly inherited susceptibility syndromes,10 primary intendance providers tin can benefit greatly from innovative educational resources.

References

-

International Consortium Completes Human Genome Project: All goals accomplished; New vision for genome research unveiled, 2004. National Human Genome Enquiry Constitute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, and Office of Science U.S. Section of Energy; 2003.

-

Eng C, Hampel H, de la Chapelle A . Genetic testing for cancer predisposition. Annu Rev Med 2001; 52: 371–400.

-

Collins F . Shattuck lecture: Medical and societal consequences of the Human Genome Project. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 28–37.

-

Petersen GM . Genetic testing. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2000; xiv: 939–52.

-

Biesecker BB . Future directions in genetic counseling: Practical and ethical considerations. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal 1998; viii: 145–160.

-

Schwartz Physician, Lerman C, Brogan B, Peshkin BN, Halbert CH, DeMarco T, et al. Impact of BRCA1/BRCA2 counseling and testing on newly diagnosed breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 1823–1829.

-

Gollust SE, Hull SC, Wilfond BS . Limitations of direct-to-consumer advertising for clinical genetic testing. JAMA 2002; 288: 1762–1767.

-

Freedman AN, Wideroff L, Olson L, et al. The states physicians' attitudes toward genetic testing for cancer susceptibility. Am J Med Genet 2003; 120A: 63–71.

-

Friedman LC, Cooper HP, Webb JA, Weinberg Advertising, Plon SE . Primary care physicians' attitudes and practices regarding cancer genetics: a comparison of 2001 with 1996 survey results. J Cancer Educ 2003; xviii: 91–94.

-

Greendale Chiliad, Pyeritz RE . Empowering primary care health professionals in medical genetics: how soon? How fast? How far?. Am J Med Genet 2001; 106: 223–32.

-

Burke Westward, Emery J . Genetics education for primary-intendance providers. Nat Rev Genet 2002; 3: 561–566.

-

Geller G, Tambor WS, Chase GA, Hofman KJ, Faden RR, Holtzman NA . Incorporation of genetics in primary care practice– will physicians do the counseling and will they be directive?. Curvation Family Med 1993; 2: 1119–1125.

-

Hofman KJ, Tambor ES, Hunt GA, Geller G, Faden RR, Holtzman NA . Physicians' cognition of genetics and genetic tests. Bookish Med 1993; 68: 625–632.

-

Elsas LJ 2, Trepanier A . Cancer genetics in primary care. When is genetic screening an option and when is it the standard of care?. Postgraduate Medicine 2000; 107: 191–194, 197–200, 205–208.

-

Emery J, Lucassen A, Potato M . Mutual hereditary cancers and implications for chief intendance. Lancet 2001; 358: 56–63.

-

Emery J, Hayflick Southward . The challenge of integrating genetic medicine into main care. Bmj 2001; 322: 1027–1030.

-

Geller Thousand, Botkin JR, Dark-green MJ, Press North, Biesecker BB, Wilfond B, et al. Genetic testing for susceptibility to adult-onset cancer. The process and content of informed consent. JAMA 1997; 277: 1467–1474.

-

American Board of Genetic Counselors. 2004. Available at: http://www.abgc.net/genetics/abgc/about/intro.shtml. Accessed January 31, 2005.

-

National Lodge of Genetic Counselors Familial Cancer Take chances Counseling Special Involvement Group Directory; 2003.

-

Cooksey JA . The genetic counselor workforce. Chicago: Illinois Center for Wellness Workforce Studies; 2000.

-

Andrews LB, Fullarton JE, Holtzman NA, Motulsky AG . Assessing genetic risks: Implications for health and social policy. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1994.

-

Holtzman NA, Watson MS . Promoting safe and effective genetic testing in the Usa: Terminal study of the Task Force on Genetic Testing. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1998.

-

Jemal A, Tiwari RC, Murray T, Ghafoor A, Samuels A, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2004. CA Cancer J Clin 2004; 54: 8–29.

-

Claus EB, Schildkraut JM, Thompson WD, Risch NJ . The genetic attributable risk of chest and ovarian cancer. Cancer 1996; 77: 2318–2324.

-

Ford D, Easton DF, Stratton M, et al. Genetic heterogeneity and penetrance assay of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in breast cancer families. The Chest Cancer Linkage Consortium. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 62: 676–89.

-

Dark-green MJ, Fost North . CD-ROM: Counseling by computer: Breast cancer risk and genetic testing. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation; 1998.

-

Green MJ, Fost N . An interactive computer program for educating and counseling patients about genetic susceptibility to chest cancer. J Cancer Educ 1997; 12: 204–208.

-

Green MJ, McInerney AM, Biesecker BB, Fost Due north . Education about genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility: Patient preferences for a computer plan or genetic advisor. Am J Med Genet 2001; 103: 24–31.

-

Dark-green MJ, Biesecker BB, McInerney AM, Mauger D, Fost N . An interactive estimator plan can effectively educate patients about genetic testing for chest cancer susceptibility. Am J Med Genet 2001; 103: 16–23.

-

Light-green MJ, Peterson SK, Baker MW, Harper GR, Friedman LC, Rubinstein WS, et al. Effect of a computer-based determination assist on knowledge, perceptions, and intentions about genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004; 292: 442–452.

-

Berry DA, Parmigiani G, Sanchez J, Schildkraut J, Winer E . Probability of carrying a mutation of breast-ovarian cancer cistron BRCA1 based on family history. J Natl Cancer Inst 1997; 89: 227–238.

-

Parmigiani One thousand, Berry D, Aguilar O . Determining carrier probabilities for breast cancer-susceptibility genes BRCA1 and BRCA2. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 62: 145–158.

-

Euhus DM, Smith KC, Robinson L, Stucky A, Olopade OI, Cummings S, et al. Pretest prediction of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation by chance counselors and the computer model BRCAPRO. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002; 94: 844–851.

-

Drupe DA, Iversen ES Jr, Gudbjartsson DF, Hiller EH, Garber JE, Peshkin BN, et al. BRCAPRO validation, sensitivity of genetic testing of BRCA1/BRCA2, and prevalence of other breast cancer susceptibility genes. J Clin Oncol 2002; 20: 2701–2712.

-

Baty BJ . Counseling past reckoner: Breast cancer take a chance and genetic testing. Am J Med Genet 1999; 86: 93–94.

-

McGee K . New media: Breast cancer counseling. JAMA 1999; 281: 1652.

-

Crowe JP . CD-ROM review: Counseling by figurer: Chest cancer risk and genetic testing. J Womens Health 1999; viii: 25–26.

-

Dabney MK, Huelsman Grand . Software review: Counseling past reckoner: Breast cancer run a risk and genetic testing. Genet Examination 2000; 4: 43–44.

-

McGee G . Beyond genetics: Putting the power of Dna to piece of work in your life. New York: HarperCollins; 2003; 96–99.

-

American Society of Clinical Oncology. Statement of the American Society of Clinical Oncology: Genetic testing for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol 1996; 14: 1730–1736.

-

Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, Mayeaux EJ, George RB, Irish potato PW, et al. Rapid guess of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med 1993; 25: 391–395.

-

Miles MB, Huberman AM . Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook, 2d ed. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, Inc; 1994.

-

Biesecker BB, Peters KF . Procedure studies in genetic counseling: peering into the black box. Am J Med Genet 2001; 106: 191–198.

-

Bernhardt BA, Biesecker BB, Mastromarino CL . Goals, benefits, and outcomes of genetic counseling: client and genetic counselor cess. Am J Med Genet 2000; 94: 189–197.

-

Fisher RJ . Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. J Consum Res 1993; 20: 303–315.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported past grant numbers R03CA70638 and R01CA84770 from the National Cancer Institute and The National Human Genome Inquiry Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (Chief Investigator: Michael Green, Physician, MS). The authors performed the design and conduct of the study; drove, management, assay, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript without the sponsor's participation. The distributor of the programme had no role in the study design or implementation. Some of the results from this study were reported at the post-obit: the 27th annual coming together of the Lodge for General Internal Medicine (May 14, 2004, Chicago, IL); the seventh annual coming together of NCHPEG/GROW (January 29, 2004, Bethesda, MD); and the 53rd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Man Genetics (Nov six, 2003, Los Angeles, CA). Nosotros would like to admit Joanne Caulfield, Dr. Andrew Baum, Dr. Norm Fost, and the genetic counselors who provided guidance and feedback on the development of the study questionnaire. Copies of the estimator programme, "Breast Cancer Run a risk and Genetic Testing," are bachelor through Medical Audio Visual Communications, Inc. Suite 240, 2315 Whirlpool Street, Niagara Falls, New York, 14305; Phone: ane–800–757–4868. Email: dwc@mavc.com. http://www.mavc.com ($49 for individuals and $99 for institutions).

Author information

Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Well-nigh this article

Cite this article

Light-green, Yard., Peterson, S., Baker, M. et al. Apply of an educational computer plan before genetic counseling for breast cancer susceptibility: Effects on duration and content of counseling sessions. Genet Med 7, 221–229 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.GIM.0000159905.13125.86

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Issue Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1097/01.GIM.0000159905.13125.86

Keywords

- genetic counseling

- breast cancer

- decision aids

- computer based education

- genes BRCA1/2

Further reading

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/gim200546

0 Response to "45 Minutes Was Spent Face to Face With the Family by a Counselor Providing Genetic Counseling"

Post a Comment